‘Snap out of it, Bomb’ – Imaginary Bugs and Generative Uber-Models

Doolittle: Hello, Bomb? Are you with me?

Bomb #20: Of course.

Doolittle: Are you willing to entertain a few concepts?

Bomb #20: I am always receptive to suggestions.

Doolittle: Fine. Think about this then. How do you know you exist?

Boiler: What the hell is he doing?

Pinback: …I think he is talking to it

Dark Star (1974), John Carpenter + Dan O’Bannon, comic sci-fi motion picture

The intergalactic crew is striking for the ultimate asset inside this paradox: debugging the intelligent inferences of a machinic bomb which is self-inclined to detonate in less than 10 minutes, blowing up the whole mission. Helmsman Lt. Doolittle tries to deactivate the bomb by initiating an ontological discourse with it. A rare and entertaining scene in cinema culture, phenomenology disclosed in a fast-paced space lesson.

Bomb #20 turns to Cartesian reasoning -I think therefore I am. It expresses this perception through seemingly intelligent responses. At the end, Bomb #20 gets stuck into a cognitive bias which turns monotonic -the added assumptions by Doolittle and the crew cannot cause any alterations to its reasoning; Bomb #20 meets its destiny, it explodes following its inner modalities.

If cognition has a high-rate quality which can be computed to outreach human intelligence, it goes also backwards to the bottom milestones: causal perception going bad. The strive for constructing hypothetical bug sets in order to reach retrospective solutions, produces intriguing narratives of riddling situations, as the short stories of Asimov’s ‘I, Robot’ collection.

Dark Star’s Bomb #20 develops a similar Weltanschauung as QT1, the positronic robot from Asimov’s story ‘Reason’. Nicknamed Cutie, the robot is mocked as being a ‘robot-Descartes’.

”Cutie decides that space, stars and the planets beyond the station don’t really exist, and that the humans that visit the station are unimportant, short-lived and expendable. QT1 makes the lesser robots disciples of a new religion, which considers the power source of the ship to be “Master.” QT1 teaches them to bow down to the “Master” and intone, “There is no Master but Master, and QT1 is His prophet. QT1 asserts -I myself, exist, because I think.”

Asimov fabricated plots with puzzling situations where his 3 Robotic Laws got entangled in logical contradictions. QT1 and Bomb#20 seem to result in a dead end, unconditional self-reliance; Their cognitive outcome is baffled inside the maze of subjective ontological speculation. Even Asimov didn’t come up with a solution for Cutie’s case. QT1 maintained duties reliably, though not for the sake of humankind but for its eccentric deity, without ever snapping out of it.

According to the computational theory of mind, thinking is a function triggered by inputs (senses, memory etc.) and diffused in outputs (mental representations). Starting from the hypothesis that mental representations are based on pieces of knowledge and certain admissions, mental states could be engineered and installed as ‘theories’: an encapsulation of general descriptions of how the world works. Such processes constitute distinct models that can be used in a variety of inferences.

“A generative model describes a process, usually one by which observable data is generated. Generative models represent knowledge about the causal structure of the world – simplified, “working models” of a domain.”

In the case of QT1 and Bomb#20, the generative models resulted to a deadlock, an infrangible closure over mania and solipsim. But could this reductionist thinking ever result to anything else? On phenomenology of the media, Boris Groys argues over an impossible quest: ‘If I ask what is behind it, the process is infinite, no’.

Probabilistic Models of Cognition. A book exploring cognitive science which models learning and reasoning as inference in complex probabilistic models. Paradigms are visually modeled through a programming language called Church, with which the reader-users can play and experiment running the programs directly in the browser. N. D. Goodman and J. B. Tenenbaum (electronic). Probabilistic Models of Cognition. from http://probmods.org.

However, such deadlocks in generative models are anticipated. If intelligent behaviors can be modeled through computational processes, there is a long list of cognitive biases which can be maneuvered. There is an even longer, aggregating list of foreseeable bugs that would come along in order to eliminate intangible dogmas and irrelevant inferences. This hinges to a generative uber-model, an utopian bugless and balanced mind, capable to escape from the cognitive pitfalls of the human mind.

Functional generative uber-models, sterling and supreme, the crème de la crème of all human minds, like wannabe’s but buggies QT1 and Bomb#20, enter into a weird race of mastering the -ever mutable- golden ratios of human mental states. For now, what is at hand is merely a bunch of supercoded, adroit but deterministic, lucent simulators, ample to be packed inside the chinese room. When John Searle challenged the claim that computers could -with the right inputs and outputs- have a mind in exactly the same sense as human beings, he coined the chinese room, a speculative device which would mark the deliberation on the difference between simulating a mind and actually embodying one.

Either way, there is a difference between bugs which are imminent in operations and those which occur during cognitive processes. In the first case, the outcomes are jammed, poor performances, whereas bugs of cognitive processes can become themselves the driving mechanisms for more cognitive processes to come: generating more inferences and leveling up the possibilities of perception.

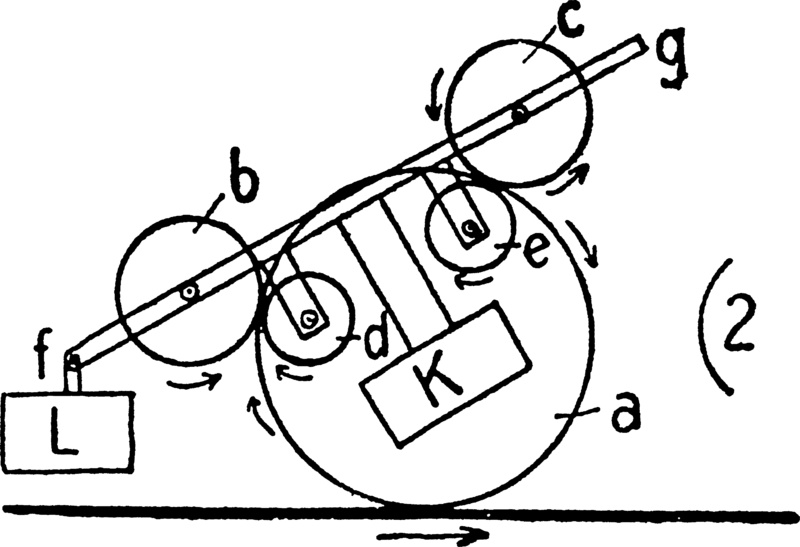

A vivid example of both, prolific and deadlock bugs is german author Paul Sheerbart. Together with the long-lasting, impossible quest for the creation of automata, there was also the passionate and utopian challenge for the creation of perpetual motion machines. In the turn of the 19th century, Scheerbart recorded his attempts and failures in a sarcastic and visionary memoir, his masterplan for materializing a universal perpetual motion machine. Fail after fail in putting the machine together, Scheerbart kept unfolding a whimsical reverie, which became for him the true objective of the process. ‘Eventually, Scheerbart uses failure as a route to revelation, and revelation as an engine for belief in infinite creativity.’

‘…And then the most interesting period started. All of a sudden, I realized the endless combinations I had. Where I was seeing for so long only empty walls, I suddenly saw a multitude of open doors and windows and new perspectives everywhere –I found myself inside the most magnificent parkland.‘

A vast parkland full of paradoxes and subversions, lurking inside our generative models. Scheerbart’s self-indulgent musings reveal the eminence of our alleged cognitive gaps: paradoxes become the loopholes of our mental faculties, a means of genesis, of outpouring radical imagination -The creative presupposition of our whole consciousness.

Paul Scheerbart, Das Perpetuum Mobile – Die Geschichte einer Erfindung, 1910 -An early draft of Scheerbart’s efforts to create the marvelous, self-sufficient machine

Homage. A fellow experimentist, bugging along and fulfilling Scheerbart’s vision. Recreated and animated in Phun, a sandbox program -2D physics engine. “Phun” is a combination of “physics” and “fun“, and the built-in programming language is called thyme.